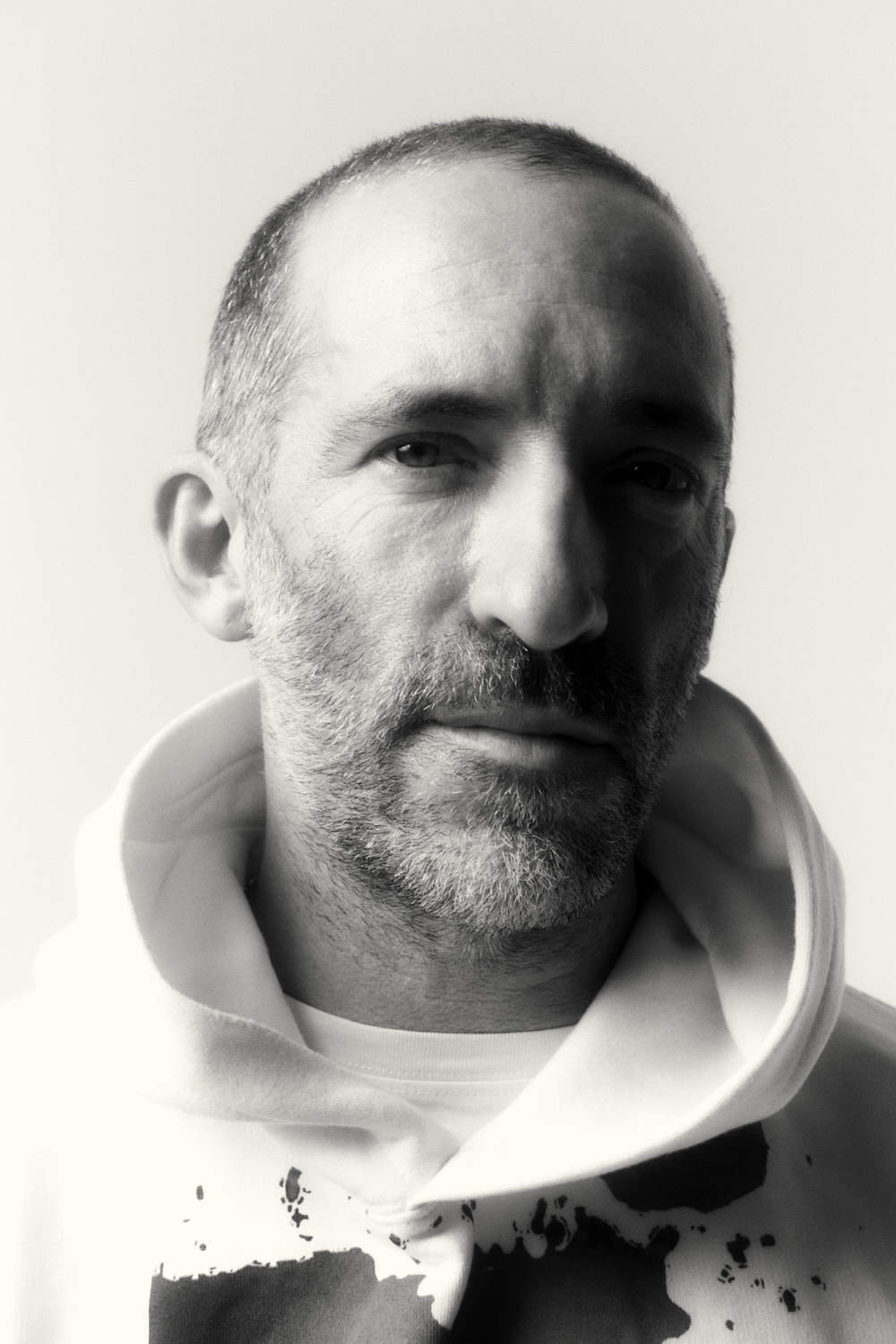

“I can’t help but break the thing” – Rudi Lewis on his career in session

Even after 30 years in the business, the iconic session stylist has the playful mind of the rebellious teenager he once was

by CATHERINE | EXPLORE > PORTFOLIOS

|

Rudi Lewis @ LGA Management |

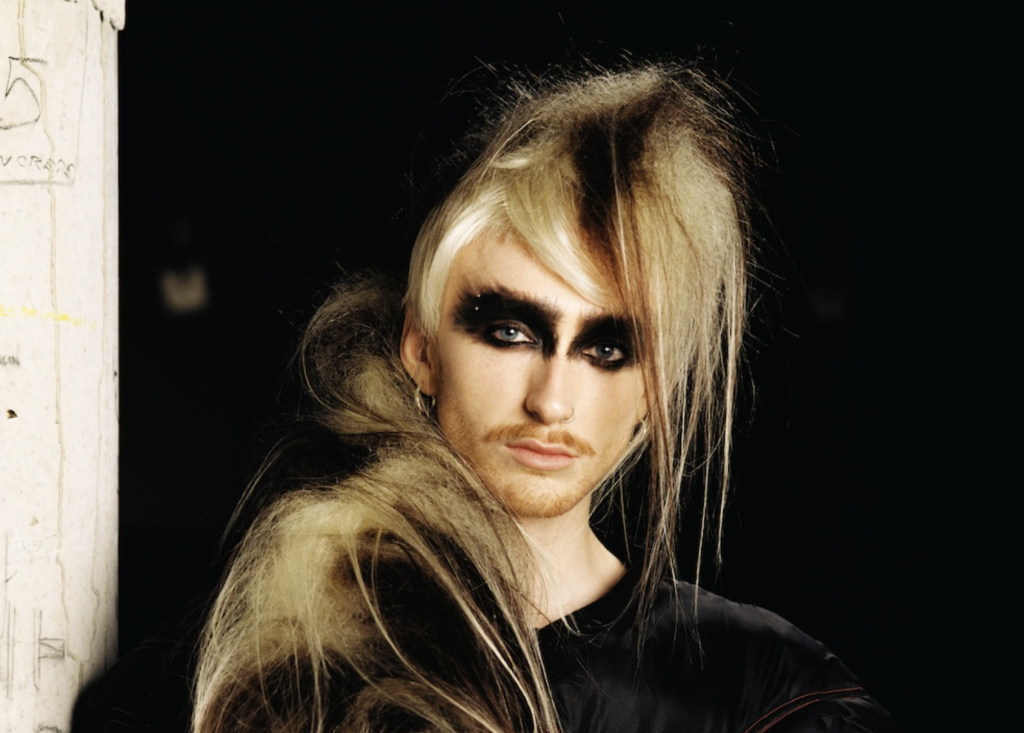

On certain jobs session stylist Rudi Lewis finds himself people-pleasing – a habit formed during his years working on clients in salons, and one he can’t quite shake off. But put him in a room with people he clicks with and off he goes – liberated, empowered and excited to create looks that pulsate with the raw energy and rebellion of the music and subculture worlds where his heart and soul have always belonged. That’s when you’ll see Rudi at his scintillating, sensational, zeitgeist-defining best – and see why brands such as Gucci, Dior and Louis Vuitton want him on their teams. Creative HEAD meets a risk-taker par extraordinaire… Damp, squalid, overcrowded – the Glasgow tenements of the ’70s had some of the worst conditions in Britain. Not the obvious background for a career in high fashion, but for young Rudi Lewis, growing up on one of the roughest estates was also where he discovered music, style, and the codes of punk that later took him to some of the most glamorous places in the world. “Where I lived, you could get beaten up for having the wrong pair of trainers, it was pretty homogeneous,” he says, “so I can still remember the first time I saw David Bowie or Adam Ant and thinking, ‘Oh, it’s okay to be yourself, I don’t have to live this life, I can be someone with my own style somewhere else.’”

|

|

Rudi Lewis @ LGA Management |

On certain jobs session stylist Rudi Lewis finds himself people-pleasing – a habit formed during his years working on clients in salons, and one he can’t quite shake off. But put him in a room with people he clicks with and off he goes – liberated, empowered and excited to create looks that pulsate with the raw energy and rebellion of the music and subculture worlds where his heart and soul have always belonged. That’s when you’ll see Rudi at his scintillating, sensational, zeitgeist-defining best – and see why brands such as Gucci, Dior and Louis Vuitton want him on their teams. Creative HEAD meets a risk-taker par extraordinaire…

Damp, squalid, overcrowded – the Glasgow tenements of the ’70s had some of the worst conditions in Britain. Not the obvious background for a career in high fashion, but for young Rudi Lewis, growing up on one of the roughest estates was also where he discovered music, style, and the codes of punk that later took him to some of the most glamorous places in the world. “Where I lived, you could get beaten up for having the wrong pair of trainers, it was pretty homogeneous,” he says, “so I can still remember the first time I saw David Bowie or Adam Ant and thinking, ‘Oh, it’s okay to be yourself, I don’t have to live this life, I can be someone with my own style somewhere else.’”

His escape route came in the form of hair. Inspired by Irvine and Rita Rusk, the super-stylish Glaswegian hairdressing duo who had won countless national and international awards and who went around the city in matching leather overcoats and oversized sunglasses, salons were springing up all around Glasgow and 16-year-old Rudi – who had always known how he wanted to look and how he wanted hair to look – found himself training at local salon Billy Smith’s in Clydebank, before qualifying at James Margey in Glasgow’s West End. “It was an oasis of cool people like I’d never seen before,” he recalls. “I loved it.” When a hairdresser neighbour left to go and work at Trevor Sorbie in London, a 17-year-old Rudi followed – and never looked back.

He chose to work at Eclipse in north London because they shot photo-collections and took part in the Alternative Hair Show. Rudi had already developed a love of image-making, thanks to a friend of his mother’s, Nick Peacock, who back home had taught him how to use a camera and develop his own photos in a dark room. Rudi is grateful for his time at Eclipse because it’s where he learnt how to run a salon but, desperate to work in Covent Garden, in 1995 he chose to move to Paul Windle’s salon because “he had work from really cool photographers such as Glen Luchford in his windows”.

It must have been an omen, because that’s where Rudi met Eugene Souleiman, who told him he loved his work and that he shouldn’t try and copy anyone else’s, and that’s how Rudi ended up assisting Eugene at the shows, and where Rudi excelled and found his niche. And that’s how a career in session was born.

The Motif, photography by Casper Wackerhausen-Sejersen

How important to your session career were those early years working in salons?

My time in the salon was genuinely formative in so many ways. For example, when I was at Eclipse I assisted an Afro hair specialist called Randolph Gray, who did tonnes of clients all day long, so I had to learn how to work with Afro hair. At that time it was unusual for white hairdressers to have much experience with Afro hair, it was a totally separate industry in a way. But I was exposed to it quite early on in my career, and it’s meant that I’ve always been confident with all textures of hair.

Paul Windle had run the academy at Sassoon and there was a culture of very technical haircutting at [his salon] Windle when I joined. I noticed there was this guy who used to pop in now and again and do these insanely good haircuts. It was Eugene Souleiman, and he’s one of the most unique and brilliant people I have ever met in my life. After he’d seen me a few times he said to me, “Why are you trying to cut hair like everybody else?” And I was like, “What do you mean?” And he said, “Don’t try to be like them because you’ve got your own thing going on. You’ve got great hands.” And that was the most inspirational thing anyone had ever said about my work. And funnily enough I had actually suffered from impostor syndrome at Windle, because I felt like I wasn’t as good or as technical as the other stylists there.

When Eugene asked me to come and do some shows with him, I had to ask Paul for permission because I was a very busy stylist. At that time, the session world was very separate from salon – if you wanted to become a session stylist, it was either because you thought you were better than anyone else in the salon or you just wanted to get out of there. But Paul saw that it could be very interesting if we could learn session techniques and bring them into our work in the salon, that it would be a very good USP for the business. And it was around this time we also connected with Bumble & bumble (Windle went on to become a distributor for the brand) and its entire product range was based on session. We also had magazine journalists coming into the salon and they would say, “Oh, can you fix the hair on a shoot we’re doing for The Face this weekend?”, so I was starting to do a lot of shoots, as well. When I look back, those were the golden years at Windle and I am still very proud of that time because I think we created a direction in hair salons and hairdressing that was totally new and really very good. We produced a lot of excellent hairdressers who went on to do great things.

“You can get these jobs where you get a chemistry going and that can be really liberating”

i-D, photography by Josh Olins

Vogue Scandinavia, photography by Gregory Harris

That’s a heck of a start, assisting Eugene. So where did things go from there? How did you get your first break as an independent?

After I left Windle, I moved to Sweden to be with my partner, but I kept flying back to London to do clients. By that time, it was becoming more acceptable to flick back and forth between salon and session, so I was freelancing at salons like Michael Van Clarke, who was happy for me to juggle clients in between shoots, and Daniel Hersheson, whose son Luke was also getting started in session around then. I joined an agency that was mainly based out of New York and things blew up very quickly. Within a matter of weeks I was shooting my first covers for Vogue and was even commissioned to shoot a hair story for Paris Vogue, which was mind-blowing at the time!

How confident were you in your work, given how quickly things were moving?

Even to this day I always have a slight panic before I go on a job, and I think I need it. I don’t like it, and it makes me uncomfortable, but I think that if I didn’t have it, I would probably get lazy. But then you can get these jobs where you just click with the rest of the team, you get a chemistry going and that can be really liberating, so it really depends on the job. If I’m going into a job with people I’ve worked with a lot and they clearly like what I do, then I feel free to push myself more. But when I’m working with a client for the first time, my tendency is to go back to ‘hair salon guy’ and approach it like a consultation and ask them about their expectations so I can deliver what they want really well. I’m quite a thorough consultant [he laughs]. But I will probably always have a bit of impostor syndrome.

How would you describe your aesthetic? What is it that people book you for?

I don’t really like perfection. I like there to be elements present in the hair that are human – something that you know the hairdresser did, like a little tuft of hair that goes that way or one that goes over there. I always need to break the thing. Even when I do the most perfect shape, I’ll just do one little tweak, I can’t help myself. My silhouettes are coming from things that I think are cool and rooted in subculture. So, people like Morrissey, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Kurt Cobain, Nick Cave, Marianne Faithfull… you know, just iconic musicians that I grew up listening to. Even when I’m working on a glamorous high fashion shoot, I tend to reinterpret those looks. I also do some abstract work, creating wigs out of materials that aren’t hair, like buttons or safety pins, but the silhouette is always a recognisable hairstyle, like a bob, or a beehive, but in plastic or something. I want people to see that. Maybe they don’t, but it’s there if you look.

Out of Order, photography by Sølve Sundsbø

Self Service, photography by David Armstrong

And how have you managed to stay true to your aesthetic throughout your career?

It’s something that I’m more aware of now. I think earlier in my career I did projects that were more commercial or high glamour, and I went along with it because I was working with all the big names. But looking back, I always felt that I didn’t really belong. So, I made a conscious effort to go back to my roots and do projects that felt authentic to me. It was around this time that I began to contribute to Beauty Papers magazine, which was looking for work that was coming from a less obviously commercial place, less product-oriented. The projects I’ve done for them have been very much my aesthetic and it was a real turning point for me because it gave me the opportunity to showcase a more intelligent kind of hair story. So, nowadays I’m quite careful only to take on projects that are true to my style.

Session is a competitive industry. How do you stay sane?

I used to be pretty competitive. I would flick through magazines, and it would make me feel envious, thinking, ‘Why didn’t I get that job?’ or whatever. But one of my best friends is a stylist who has gone on to become one of the biggest names in the fashion industry. I remember having a conversation with him some years ago and he said, “The funny thing is, it’s never how you think it is. So, sometimes you don’t get a job and you think it’s because you’re not good enough or someone doesn’t want to work with you. And it’s totally understandable that you would think like that because you don’t have all the information. But I’m in that room when the conversations are taking place, and it literally could be just a random reason why someone else gets the job. It’s not personal at all”. So, that was good to know and understand, I do try to keep a healthy distance from these things nowadays. I do feel like I deserve to be where I am. Sometimes you don’t get the job and a week later something else great comes in.

The Last Magazine, photography by Nathaniel Goldberg

Who do you enjoy collaborating with? Who brings out your best work?

When I work, I’m always stood right next to the photographer, constantly touching the hair and changing things because I know photographers respond to that. I see how light falls on the hair and I see how the hair might affect the light on the face, things like that. A lot of hairdressers are thinking about their hairstyle; but I’m thinking about the picture. I’ve done a couple of projects with Paolo Roversi, which was very liberating. I have also done some amazing shoots with a Swedish photographer called Julia Hetta, where I really got to push it and do some great hair. I also got to work with David Bailey, which I absolutely loved because he’s a legend. But right now I’m really enjoying working with new, up-and-coming photographers. I’m working with a guy called Sam Rock, who is just killing it at the moment, he’s an amazing talent. Another great one I shoot with is Drew Vickers, and it’s always very collaborative with him. I like it when I’m able to have a voice and some creative influence over the outcome of the shoot.

Everyone’s a photographer on social! Are you a fan?

Sometimes I feel that we’re drowning in imagery. The algorithm means that great work is getting diluted by the mediocre work that surrounds it. People barely look at things for more than a few seconds, so I think that’s a downside. It’s the constant scroll on the phone! I used to be a voracious reader, I’d read a book every week, and then because of looking at my phone there was a time when it was taking me months. And so, I just checked out from it. I wasn’t posting anything at all. Right now, we’re trying to detox in our house a little bit, so the kids get an hour when they’re home from school where they can chill and be on their iPads or whatever, and then we all switch everything off so no one’s on their phone in the evening. I just think it’s healthy, you know.

For me it’s all about doing stuff that I really enjoyed before in the analogue world, and then getting to a place where I’ve generated enough work that I actually want to post on social media. It’s why I’ve found myself this little salon-cum-studio space in Stockholm and I’m going to make it this place where every week someone comes over, a bit like a go-see, and I’m going to do their hair and then shoot them, so I generate my own imagery in a quiet, organic, real kind of way. It won’t be retouched and it will be done in my own time, not rushed, like on work shoots, just me and that person. That’s the goal for me. That’s how I’m able to compute social media.

“I see how light falls on the hair and I see how the hair might affect the light on the face, things like that. A lot of hairdressers are thinking about their hairstyle; I’m thinking about the picture”

What’s exciting you right now?

Well, my energy and focus is really on the new place. As well as being a little salon to do clients, and the portrait studio, I am planning to publish my own little books and ’zines, I’m about to release the first one, which is a collaboration with a young Scottish photographer called Rachel Lamb, we cast it and shot it all in Glasgow. I even borrowed my old boss James Margey’s salon to do all the haircuts. So, it was kind of full circle for me. I am really excited about that project because I’m not just the hairdresser, I’m the creative director and publisher too. I guess it’s a response to the digital and AI thing, I just wanted to make something tactile, that doesn’t just exist online.

What’s the biggest risk you’ve taken in your career?

Lots of decisions are difficult because you have to confront fear – your own or someone else’s – but I guess moving to Sweden would have to be up there. After 20 years in London, it was a real gamble. It’s tough to maintain a successful career, learn a new language, start over, make new friends when you travel as much as I do. My new studio is also a big risk because I’ve been so transient for so long now that it’s a bit scary putting roots down. I’ve invested a lot of money, time and energy into it.

You’ve spent a long time in the session world. Any advice for someone just starting out?

There’s something very authentic and approachable about the new generation of hairdressers working in session, and what they’re doing is actually informing a lot of the work that more established artists are doing. You’ve got all these gender-fluid, non-conformist kids who have all that language around their work and everybody wants to be in that space now, right? I mean, traditionally, all the big ideas would come from the fashion industry and trickle out into society but now those ideas are coming from young people and fashion is trying to keep up. So, what I would urge young session stylists to do is shoot with your friends, own your identity, show it through your skills because what you’re doing is interesting and it is changing the world. And it looks great!